- Home

- 2021

- January 2021

- Professor King? Celebrating the Legacy of a Civil Rights Leader and Teacher

Professor King? Celebrating the Legacy of a Civil Rights Leader and Teacher

In 1954, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was confronted with one of the most difficult decisions of his young life. Only a year away from completing his PhD at Boston University, he had already fielded several promising offers from employers who recognized his sparkling intellect and gift for public speaking. The offers came from two groups: churches asking King to become their pastor, and universities hoping to employ King as a chaplain and professor. In his book Stride Toward Freedom, King describes sitting on an airplane headed to Detroit, watching “the silvery sheets of clouds below and the deep dark shadow of the blue above” (4) and wondering which path he ought to take.

In hindsight, it seems difficult to imagine Dr. King as anything else but a minister and leader of a nonviolent movement for racial justice, but the truth is he often dreamed of having an academic career, ensconced in a seminary or university teaching philosophy and theology. Even after King decided to become a minister, colleges continually sent out appeals for him to teach on their campuses, including his alma mater, Morehouse College in Atlanta.

But the most appealing offers came from the north; Dr. King and his wife Coretta enjoyed living in Boston, where they could “escape the long night of segregation” (4) that existed in the Jim Crow south they grew up in. When Dr. King returned from his trip to Detroit, he asked Coretta what she thought. She wondered about what kind of life their children would lead if they moved back home, and whether opportunities for career advancement would be as plentiful in the south. They had every reason to stay where they were.

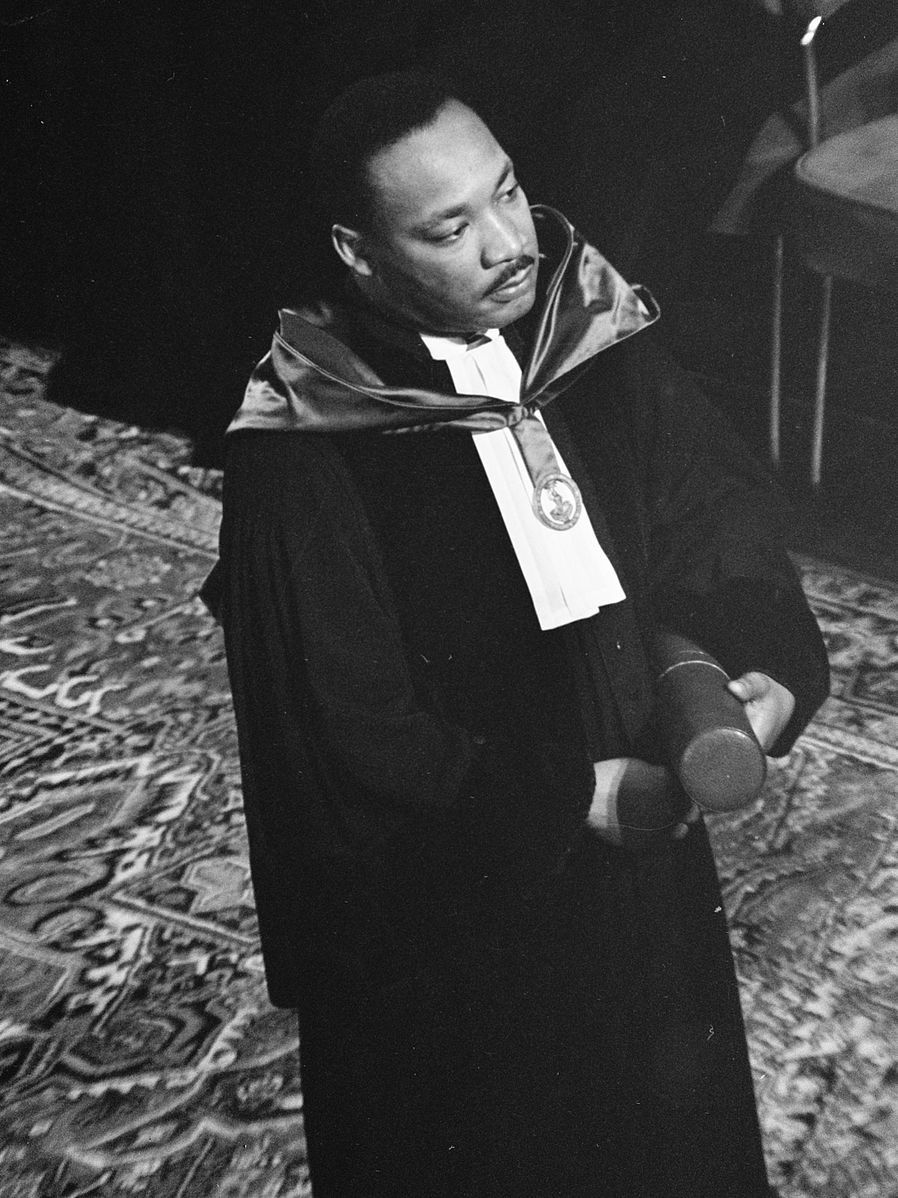

But then they made a surprising decision: they decided to move to Montgomery, Alabama, where Dr. King would become the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Within a year of accepting the job, they would meet Rosa Parks and Ralph Abernathy, help form the Montgomery Improvement Association, lead a year-long bus boycott, and begin the long journey that led King to become a global civil rights hero and Nobel Peace Prize winner.

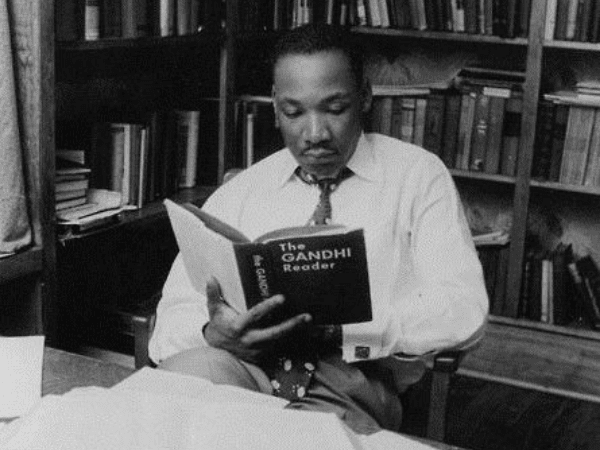

Can you imagine the alternative? If Dr. King had stayed in the north, perhaps we would not know his name. Perhaps he would have enjoyed a quiet and prosperous life as a professor at some midwestern university or northeastern seminary. Imagine what it would have been like to have Dr. King as your professor, to see him walking across the quad talking with a colleague or reading a book in a quiet corner of the library. Who knows whether he would have been happy – living in the north did not mean being free from racial prejudice and hate – but at the very least, it would have been a somewhat easier life than the one he and Coretta chose.

What then drove Dr. King to make such a curious decision? He says, “In spite of the disadvantages and inevitable sacrifices” that would come from moving to Montgomery, they figured that their “greatest service could be rendered” in the south, and they felt they had “something of a moral obligation to return – at least for a few years” (7-8).

Three things strike me in this remarkable statement, which I hope you will contemplate today as you celebrate Dr. King’s life. First, see how Dr. King harbored the aspiration to eventually go back to academia. He had been thinking deeply about teaching and learning all his life; at only eighteen years old, he published an essay in his school newspaper called “The Purpose of Education,” which is still widely quoted today. In that piece, he said that the “true goal of education” is to develop not only students’ intellect but also their character, to give them “not only power of concentration, but worthy objectives upon which to concentrate” (124). Often when Dr. King was arrested for an act of civil disobedience, he would ask his assistant to bring him a hefty stack of books which he had been unable to read while leading demonstrations across the nation. He was a true intellect, and for those of us fortunate enough to write papers or experiment in a lab, it’s a reminder that we should not take the privilege of academic work for granted.

you celebrate Dr. King’s life. First, see how Dr. King harbored the aspiration to eventually go back to academia. He had been thinking deeply about teaching and learning all his life; at only eighteen years old, he published an essay in his school newspaper called “The Purpose of Education,” which is still widely quoted today. In that piece, he said that the “true goal of education” is to develop not only students’ intellect but also their character, to give them “not only power of concentration, but worthy objectives upon which to concentrate” (124). Often when Dr. King was arrested for an act of civil disobedience, he would ask his assistant to bring him a hefty stack of books which he had been unable to read while leading demonstrations across the nation. He was a true intellect, and for those of us fortunate enough to write papers or experiment in a lab, it’s a reminder that we should not take the privilege of academic work for granted.

As for Dr. King’s plan to be a minister for only a few years, well, we know all too well what it’s like to have circumstances change our plans, don’t we? I wonder what Dr. King would say about the shift we made last year to remote instruction, or how our lives were disrupted by the pandemic and the racial reckoning occurring in our nation. As a younger man, Dr. King reminds me of first-year students who come to my office with their entire lives meticulously planned out in front of them. As they predict how every piece of their plan will fall into place to help them reach their dreams, I quietly nod and smile. After all, it’s good to make plans: indeed, our Falcon Maps initiative at UTPB is designed to help students plot the most efficient path to complete their studies. But King’s life was full of interruptions and disruptions, and I think if he were here with us today, he would tell us to not to be discouraged if life doesn’t go exactly how we envision it, but to transform our dark yesterdays into bright tomorrows.

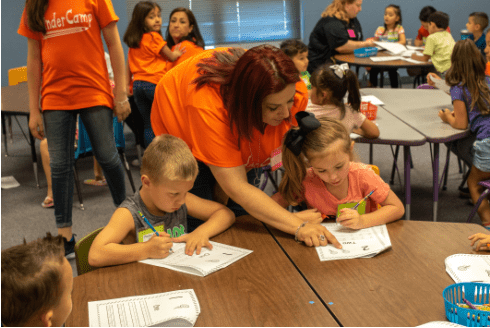

Finally, I’m inspired by how the determining factor in Dr. King’s decision was where he could provide the greatest service to others. Often when students choose a major or career, they begin by thinking about how much money they can make, or where they will be able to live, or even where they can best employ their talents. Serving their communities doesn’t initially factor in. But Dr. King believed that service was the path to true joy and greatness: “Everybody can be great,” he said, “because everybody can serve” (“The Drum Major Instinct”). And though he said “you don't have to have a college degree to serve,” I have been delighted this past year to see members of this university go the extra mile in serving others. From the courageous work of our nursing students to help our community stay safe during the pandemic, to the heroic efforts of our faculty to transition to new instructional modalities, to the tireless service of our staff outside the university’s walls, I am surrounded by servant leaders, and it makes me proud to be a Falcon.

As we establish the Center for Engaged Teaching, Learning, and Leadership on campus later this spring, I hope to bring to it the same spirit of servant leadership that Dr. King exhibited. Indeed, as I look back on that fateful flight to Detroit, when Dr. King looked down and decided the goal of his life would be to serve those who were under the dark clouds of segregation and racism, I realize that though he never became a professor in his time on earth, nevertheless, he’s one of the greatest teachers I’ve ever had.

Works Cited

King, Martin Luther, Jr. “The Drum Major Instinct.” A Knock at Midnight: Inspiration from the Great Sermons of Martin Luther King, Jr. IPM, 1998, pp. 169-86.

---. “The Purpose of Education.” The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Volume I: Called to Serve, January 1929-June 1951, edited by Clayborne Carson, University of California Press, 1992, pp. 540-42.

---. Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story. Harper & Row, 1958.